THE years 2019 and 2020 have certainly been strange ones for fluke, writes Matt Linnett of Millcroft Veterinary Group.

In 2019, XLVets Fluke Sentinel Project took place. This project blood-tested lambs on high-risk fluke farms for antibodies to fluke, up and down the country. To find out more about the study visit, www.xlvets-farm.co.uk/fluke-sentinel.

One thing the Covid-19 pandemic has done, is develop a mainstream understanding of antibody tests. If you have antibodies to Covid-19, you have met the virus or been vaccinated against it.

The same rings true for lambs with antibodies to fluke. Lambs with fluke antibodies tell us that the stock on that farm has been exposed to fluke and we can justify fluke treatment.

More interestingly though, it can also give a rough idea of when they met fluke. Antibody tests go positive two to four weeks after exposure, so regular testing can identify when the flock has met fluke.

Due to the nature of flukicides, with the exception of Triclabendazole, which is only effectively killing fluke older than five weeks old, this information is extremely useful.

For example, if you are using a flukicide other than Triclabendazole, it is likely going to be ineffective on a flock in which lambs do not have antibodies. No antibodies means no fluke older than four weeks.

Triclabendazole resistance is a serious concern and we diagnose resistance on a few more of our farms every year. I think the best use of fluke antibody blood tests is on farms with Triclabendazole resistance. By finding out exactly when the flock is meeting fluke, we can calculate the earliest timing for non-triclabendazole flukicides eg Closantel.

At Millcroft in 2019, we saw one of our “flukiest” farms meeting fluke for the first time in early December based on blood testing lambs every two weeks from September. This allowed the farmer to hold off his fluke treatment until his flock had actually met fluke.

All the while, his neighbours had been giving numerous pre-tupping fluke doses from September. All of which were a complete waste of time and money. Remember, flukicides have no persistence so there is absolutely no benefit to early treatment.

The 2019 results were so strange that we took the XLVets Fluke Sentinel Project and ran it in our patch over 2020 with fascinating results.

The map pictured shows the 2020 results, with traffic-lighted farms showing roughly what month flocks met fluke. These farms were all blood-testing regularly, approximately every two to four weeks, and testing stopped once we found a positive antibody result.

As you can see, there is a good mix of fluke challenge. This highlights the importance of testing on your own farm and why a “one size fits all” approach simply doesn’t work.

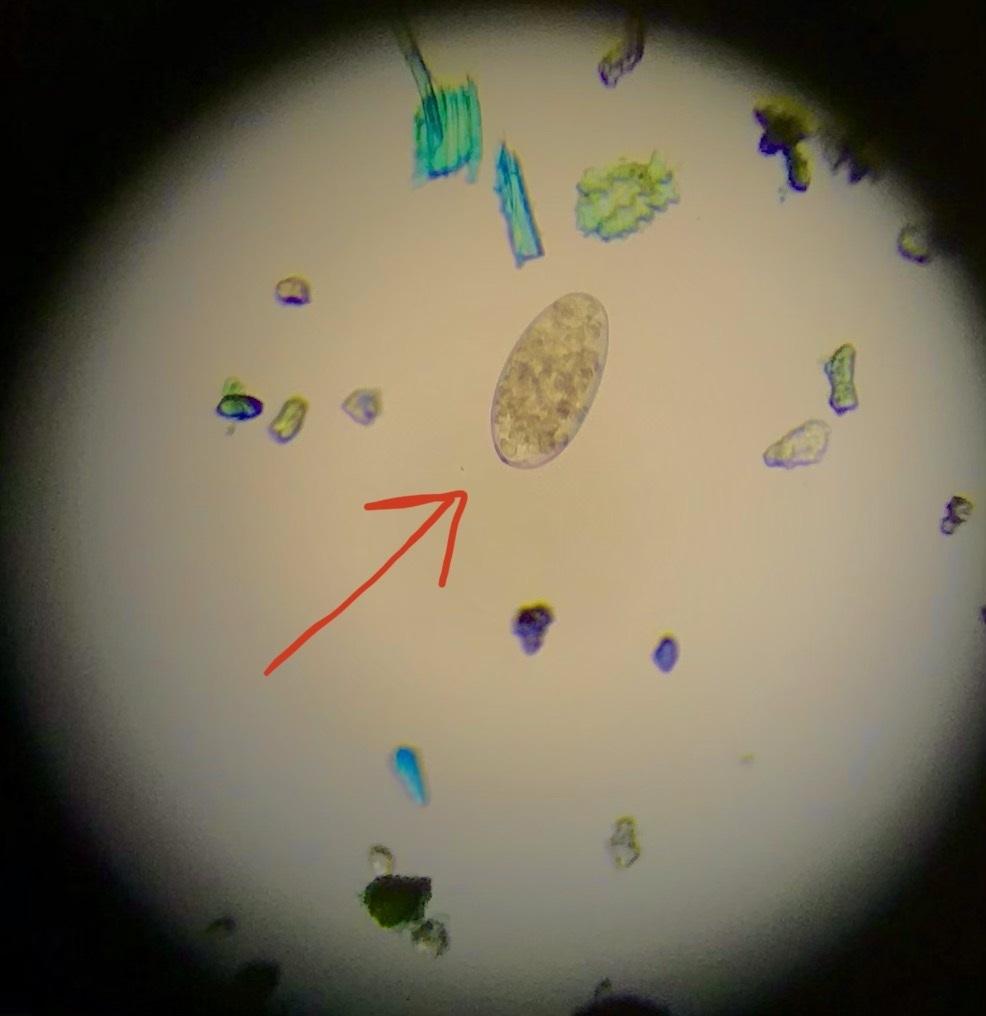

Worryingly, the late fluke challenge in 2020 has meant a number of flocks, despite multiple fluke treatments are seeing fluke “slip through the net”. Pictured is a fluke egg found in a muck sample from a ewe tested last week. This ewe was not pale, she didn’t she have any swelling around her jaw nor was she particularly thin. This ewe had been given Triclabendazole in late October and Closantel in late December but both treatments were likely far too early and adult egg-laying fluke have survived.

Thankfully, the flock was a month off lambing so all the girls can get treated and, hopefully, no knock on effects of poor colostrum leading to more lamb disease, poor recovery post-lambing or Twin Lamb disease will be seen.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here